Authored by Prasaanth Balraj, AI Transformation Lead, Wadhwani AI Global

Every 20 seconds, tuberculosis (TB) claims another life. For most people, TB feels like a disease we should have left behind decades ago. Yet in 2024, more than 10 million people still fell ill, and 1.3 million died- with the heaviest toll in the Global South, where health systems remain strained and are strained and diagnostic tools sc remain scarce.

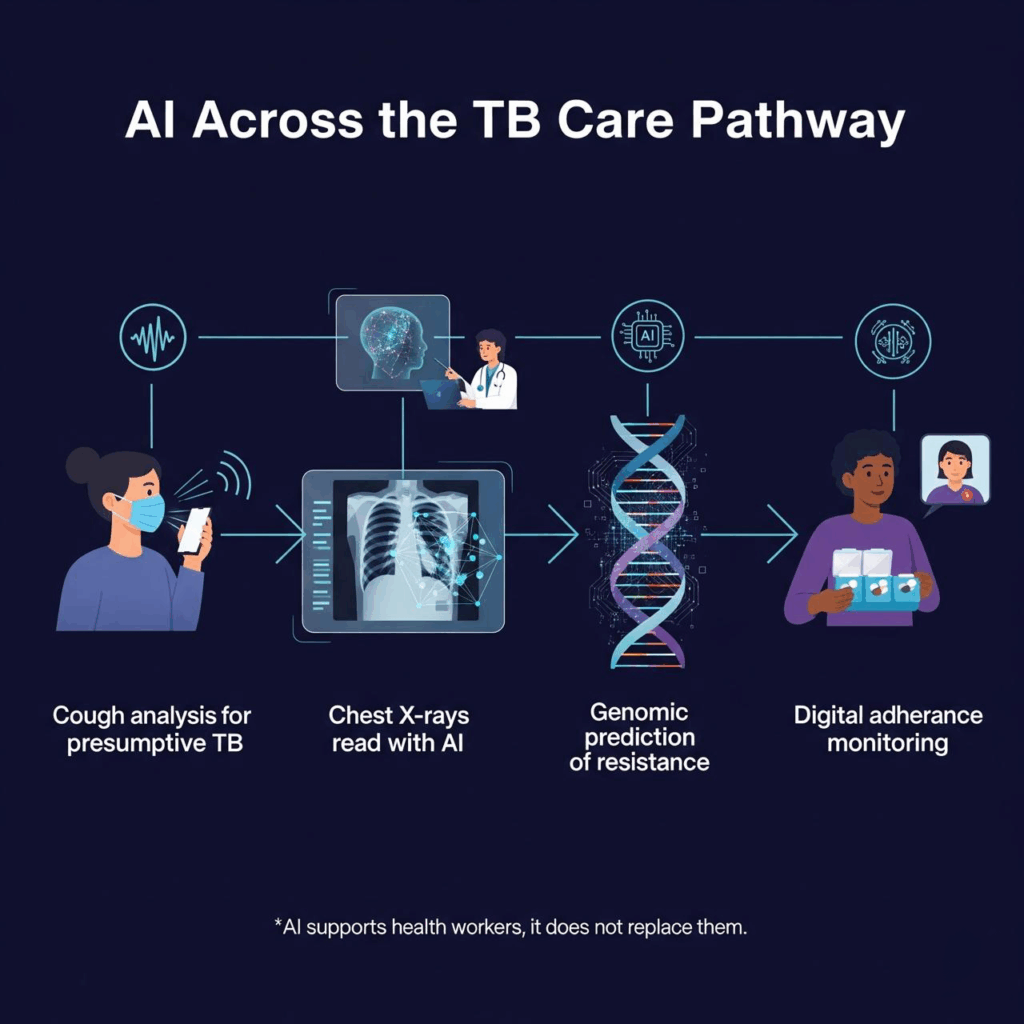

What has changed in recent years is not the scale of the epidemic but the tools available to confront it. Between 2021 and 2025, artificial intelligence (AI) shifted from pilots to integration in real TB programs. No one expects AI to replace health workers. The real test is whether it can help them detect cases earlier and faster, diagnose more accurately, and keep patients on treatment.

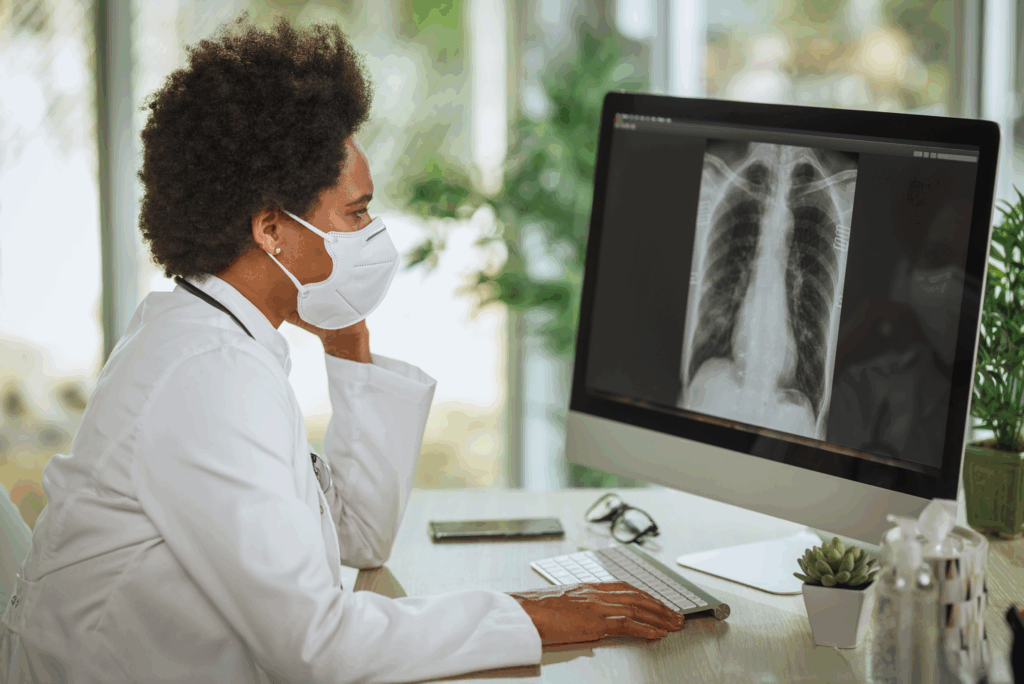

One of the most promising areas is early screening. Researchers are training AI to recognize TB patterns in cough sounds, effectively turning a smartphone into a potential triage tool. Others are using algorithms to interpret chest X-rays, flagging abnormalities with accuracy comparable to radiologists. These advances are critical in places where specialists are few and distances to clinics are long.

Drug resistance is a major obstacle to ending TB, and it is also being addressed. By analyzing molecular and genomic data, AI models are learning to predict resistance patterns within hours rather than weeks. This allows doctors to select the right drugs sooner, cutting the risk of treatment failure and ongoing transmission.

Treatment monitoring is another breakthrough. Digital tools from video check-ins to smart pillboxes and AI-powered reminders, are improving adherence compared to traditional directly observed therapy. For a disease that demands months of medication, these small improvements can mean the difference between cure and relapse.

For all the progress, the reality is more complicated. Most AI tools perform best in the settings where they were trained, but often falter elsewhere. Few have undergone rigorous external validation across diverse populations, children, or people living with HIV.

System bottlenecks are another barrier. An algorithm may flag a presumptive case, but if confirmatory tests are unavailable or treatment out of reach , the benefit disappears. Infrastructure limits such as unreliable electricity, patchy internet, and a shortage of trained staff can stall even the most promising pilot

Regulation and equity also loom large. Only a fraction of AI diagnostic tools have secured official approval, leaving countries unsure how to integrate them safely. And unless these innovations reach rural and underserved communities, they risk deepening the disparities they aim to fix.

The next wave of AI in TB won’t be about isolated apps. Real breakthroughs will come from multi-modal systems that integrate cough, X-ray, and clinical data into a single pathway. Such approaches can balance the weaknesses of any one tool, improving accuracy and reliability.

Local innovation will also matter. Tools trained on representative data from African and South Asian populations will perform better and earn greater trust. Increasingly, Global South collaborations are pooling data, running joint validations, and building capacity to maintain and improve AI systems locally.

On the policy side, momentum is growing. In 2021, the World Health Organization recommended computer-aided detection software for TB chest X-rays. Since then, countries from Kenya to India have begun integrating AI into their national programs, often in partnership with community health workers and mobile screening units. These efforts show that scale is possible when technology is embedded in the health system rather than bolted on as an afterthought.

AI will not end TB on its own. But used wisely, it can tilt the odds by helping health workers detect more cases,begin treatment sooner, and support patients through the long course of therapy. For the millions still affected each year in the Global South, that shift is not about hype. It is survival.